Kopikuz

INDUSTRIAL GIANTS: GENESIS

The early industrial development of Kuzbass is connected with the Joint-Stock Company of the Kuznetsk Coal Mines aka Kopikuz (1912 – 1919).

The main shareholders of Kopikuz were Russian and French banks. Its executive board was headquartered in St. Petersburg while the main office was located in Tomsk.

The founders of Kopikuz planned to transform Kuzbass into a powerful industrial complex that would trigger the development of the Urals and Siberia.

In a mere seven years Kopikuz conducted a geological research of the coal basin, built mines and a railway that connected Kuzbass with the Trans-Siberian railroad, started building a by-product coke plant in Kemerovo and a metallurgical plant in Kuznetsk.

Unfortunately, the turbulent historical conditions prevented the Kopikuz executives from realizing their far-reaching plans. However, they managed to create an industrial framework that would turn Kuzbass from a remote Siberian province into the largest industrial center of the country.

“Let’s make Kuzbass another Donbass!”

The foundation of KopikuzToday Kuzbass is known as one of the largest coal basins in the world and an important industrial center of Russia.

But some 100 years ago it was a remote Siberian province. Moreover, it belonged to the Tsar family and, like any royal property, was managed from St. Petersburg by a special body called His Imperial Majesty’s Cabinet. Such medieval form of feudal property deprived the region of any prospects for industrial development because private industry was forbidden on Cabinet lands.

In the late XIX century, the Cabinet made several attempts to attract private capital to the industrial development of its lands, but they ended in failure. The vastness of the territory, its scarce population and harsh climate scared potential industrialists away. The industrialization of a distant, backward region demanded huge investments to build the entire necessary infrastructure from ground zero: railways, housing, hospitals, schools, etc.

It was the Kopikuz Joint-Stock Company that laid the foundation for the rapid industrial development of Kuzbass.

The executives of Kopikuz, which became one of the largest monopolies in Siberia, put hand to the plough: they attracted large capitals, used connections in the highest circles and invited talented specialists to the development of the unique natural resources. During the brief period of its existence (1912 – 1919), the company saw a world war, a revolution and a civil war. Nevertheless, Kopikuz provided the basis for the future industrial complex.

The initiator of Kopikuz, full private councilor Vladimir Fedorovich Trepov *, was a prominent political figure of his time: a member of the State Council of Russia, the vice-governor of Turkestan and the Governor-General of the Tauric Province (which included the modern day Crimea). He belonged to the Russian political elite and had extensive ties at the royal court, which allowed him to obtain a monopoly from the Tsar on the development of coal deposits in the Altai mountain district in January 1912. The only condition was that the enterprise had to be a joint stock company.

Russian banks refused to finance Trepov's bold project, so he found investors in Paris. The French banks, the largest of which was the Societe Generale Bank, created the Altai-Siberian consortium to start the Kuznetsk Coal Mines JSC.

(Vladimir Nikolaevich Kokovtsov, the then Chairman of the Council of Ministers, stressed the significance of Trepov's contacts with French banks. He said that Trepov, in pursuit of his personal goals, prepared the French banking circles for the joint railway loan of 1914, which financed the construction of 9 railways all over Russia).

In order to ensure the profitability of their investments, French bankers sent a group of mining engineers to Kuzbass in April 1912. Trepov, who accompanied them in their journey, recalled: “During our first visit to the concession in 1912, the French engineers and I had to make our way on horseback, by boats and often on foot over barely passable wilderness." A report on this trip was published in Paris under the title "A Trip to the Altai (Siberian) private domains of His Majesty the Emperor of Russia" (G.Gromie, L.Barillon, Mission en Altai (Sibiria) dans le domaineprive SML, Empreur de Russie, Paris, 1912).

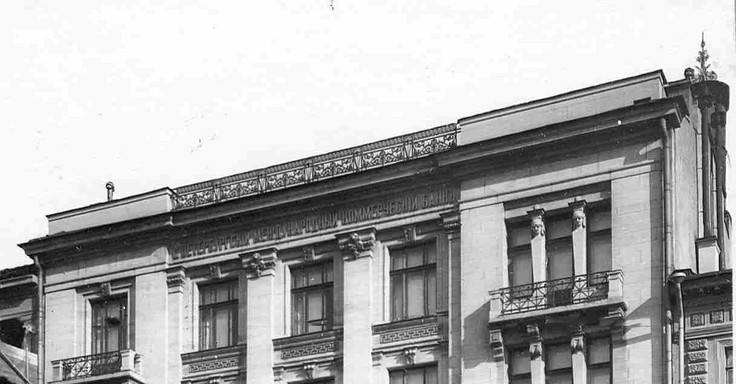

French banks agreed to finance the enterprise only if a Russian bank joined the business. As a result, the two largest banks of Russia joined the consortium, i.e. the Russian-Asian Bank and the Petersburg International Commercial Bank. The president of the latter, Sergei Stepanovich Khrulev, became Trepov’s co-chairman in Kopikuz. Subsequently, Russian banks took the leading positions in the Company.

The basic capital of the company was established as 6 million rubles and was divided into 60,000 shares of 100 rubles each. All in all, Kopokuz issued its shares 4 times).

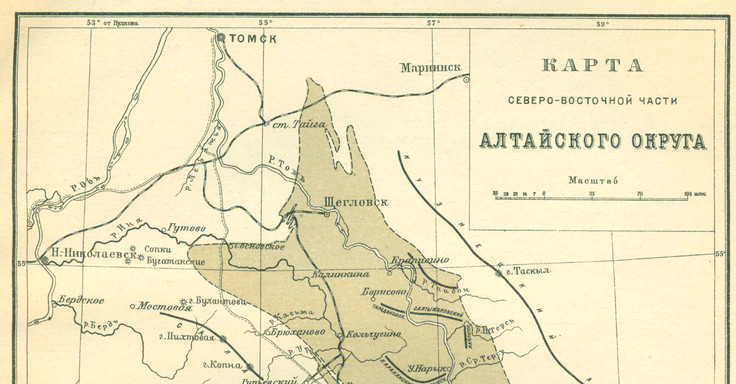

On October 19, 1912, the Kopikuz executives and the Cabinet signed a treaty. Kopikuz got a 60-year concession for the entire area of the Cabinet lands in the Altai District, i.e. Tomsk, Yenisei and Irkutsk provinces. That was an entire state between the Ob and the Tom’.

Kopikuz was obliged to pay the Cabinet 0.5 kopeck for each pood (16 kg) of extracted coal. The agreement and the Kopikuz charter were approved by Emperor Nicholas II, the owner of the transferred territories.

The Executive Board of Kopikuz was headquartered in St.Petersburg and only included representatives of Russian financial circles. V.F. Trepov was elected its chairman. The position of Managing Director was offered to mining engineer Joseph Iosifovich Fedorovich, the best mine director in Donbass.

The Kopikuz executives planned to create a powerful fuel and metallurgical complex in Siberia. In their opinion, the Kuznetsk Basin was to become the foundation for industrial development of the Urals and Siberia, just like the Donetsk Basin in the European part of Russia.

The railroad framework of Kuzbass

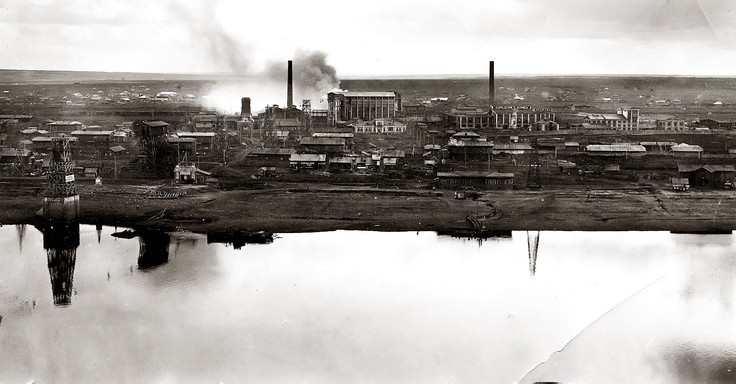

The Trans-Kuzbass railroadThe Kopikuz Joint-Stock Company began operating in Kuzbass on January 4, 1913.

The executives started with the construction of the railway branch that would link the Kopikuz enterprises to the Trans-Siberian Railway. Two branches connected the Kolchugino and the Kemerovo mines with the Yurga station on the Trans-Siberian line. And it was not just some purely industrial narrow-gauge railroad but a standard railroad line of normal general-purpose gauge, which immediately gave the branch state significance.

To finance the construction, Trepov and Khrulev founded the Kolchugino Railway Joint-Stock Company, which was in fact a structural subdivision of Kopikuz. On January 2, 1913, the Emperor approved the Company's Charter: Kopikuz could exploit the road for 81 years, after which it would be returned to the state. Besides, the government had the right to redeem the road after 25 years from the date of its opening.

Kolchugino Railway JSC became one of the 23 new railroad societies created by the 1905 year law "On measures to attract private capital to the railway construction in Russia".

Considering the state importance of the Kolchugino railway as a longitudinal branch of the Trans-Siberian railroad, the government granted Kopikuz with great privileges.

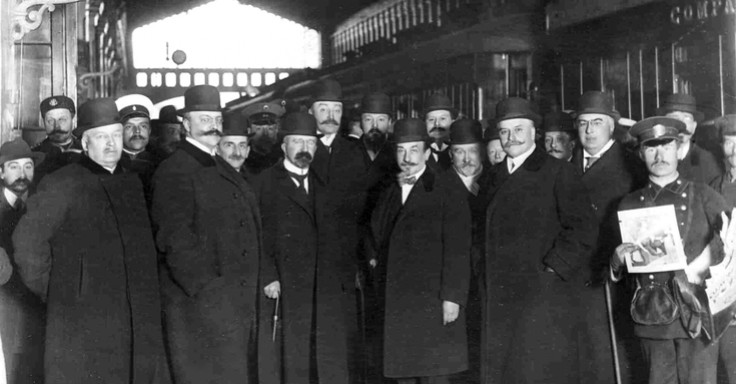

The railroad was opened for goods traffic in September 1915. Trepov and representatives of the Board of the International Commercial Bank opened it officially on July 6, 1916.

Kopikuz continued railway constructions after the Emperor issued a decree "On the alienation of land for the construction of railway lines from the Kolchugino station through the city of Kuznetsk to Tel’bess, and from Kuznetsk to Bayunovo station of the Altai Railway" (April 23, 1916). But at the end of 1918 the work stopped because of a lack of funding.

The complicated political conditions did not allow Kopikuz to implement its railway construction program. But the Company managed to do the most important thing, i.e. to link Kuzbass to the Trans-Siberian railroad, which opened Kuznetsk coal the way to the markets of Siberia and the Urals.

«Coal is the bread of industry»

The MinesKopikuz specialized in coal mining. By 1913, the demand for coal had sharply increased, as the Russian industry was beginning to shift from charcoal to this new type of fuel.

The Cabinet granted Kopikuz with two low-power mines: the Kolchugino mine and the Kemerovo mine. In a short time, the Company turned them into modern large enterprises by investing more than 12 million rubles in modernization and employing 4,467 workers (1916). The new shafts were equipped with steam engines.

The surface buildings, i.e. the surface facilities of the Central mine, the jetty, the main office building, the residence of the manager, and the hospital, were erected from rustic sandstone, or "wild stone", as it was called. Parallel to modernizing the two mines, the Company started constructing new mines in the south of Kuzbass, where new thick seams had been discovered.

In the period between 1913 and 1917, Kopikuz increased its coal production 15-fold. Its main consumers were various Ural factories and the railway, as well as local shipping companies, private enterprises, and steam mills.

Kuzbass: the second discovery

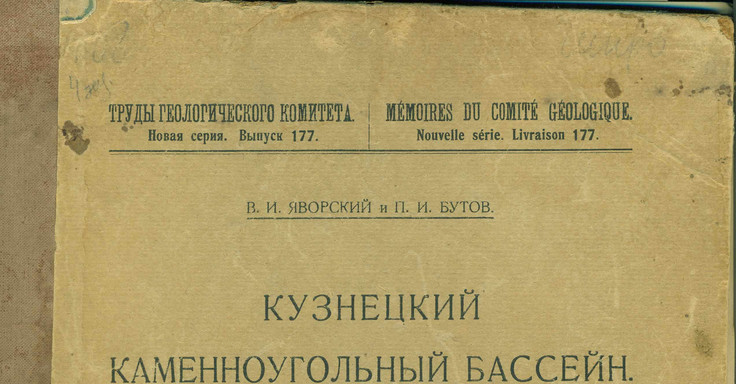

Researching Kuzbass geologyBy the beginning of the XX century, the Kuznetsk coal basin remained almost unexplored. The Cabinet gave Kopikuz 16 million dessiatines (1 dessiatine = 2.7 acres) of taiga, marshes and wastelands. The Company had to explore the vast territory to identify coal fields suitable for industrial exploitation and to determine the location for new mines.

Kopikuz handled the matter by organizing a large-scale research of the Kuznetsk coal basin. They invited Leonid Ivanovich Lutugin * to lead the work. Lutugin was a professor at the St. Petersburg Mining Institute and could be called the founder of Russian coal geology.

His team came to Kuzbass in May 1914, and they were astounded by the very first research results they obtained. They found out that the coal reserves of the basin were not 12.5 billion tons of coal, as expected, but 250 billion tons. Eventually, they assessed the local deposits as 400 billion tons. One of the geologists, Alexander Alexandrovich Gapeev, wrote: "It took us a year to realize that what we were dealing with was not some negligible secondary coal basin, but one of the world's largest coal deposits."

The geologists discovered that the richest seams of the basin were concentrated in the south of Kuzbass, and that was where Kopikuz expected to transfer the main coal mining to.

Lutugin died in 1915 in Kuzbass, but his team continued the exploration and published the first book with their research results in 1927.

Up to 1917, all geological explorations in the area were funded by Kopikuz. This was the first systematic study of the Kuznetsk coal basin, which made it possible to establish the true extent of its natural resources.

Import phase-out

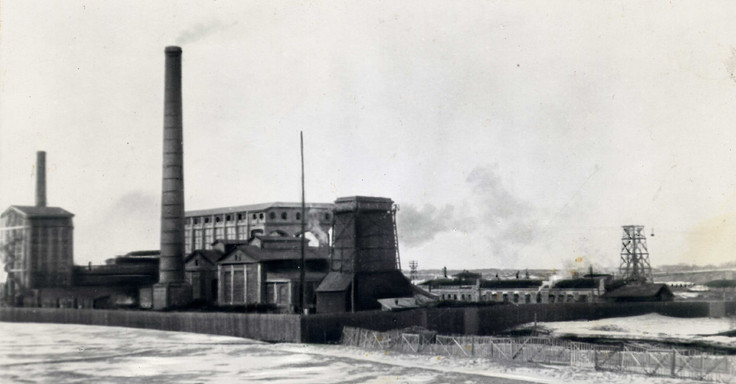

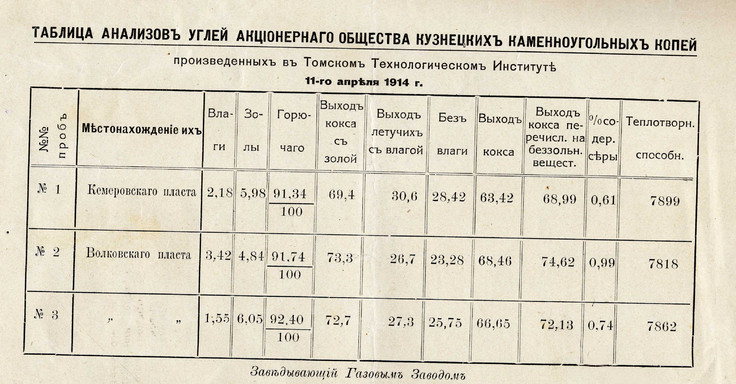

The by-product coke plantKopikuz planned to build the first Siberian coke oven plant at the Kemerovo Mine. Coking coal was necessary for the future metallurgical plant they also intended to build, and the sale of coking by-products was expected to be very profitable. The most important of these products were benzene and toluene, which could be used as raw material for explosives.

World War I boosted the process: it turned out that explosives were mostly imported to Russia from Germany, its main enemy in the war. The state had to develop a program for the creation of the national petrochemical industry. 26 plants were to be built in the Donets coalfields, but Trepov used his connections in the government for the Kemerovo plant to be included in the program. Eventually, it received a loan of 2 million rubles.

The project of the coke plant was purchased from the Belgian firm Olivier Piette for 250,000 rubles in gold, but no foreign firm agreed to build coke ovens in the harsh Siberian climate.

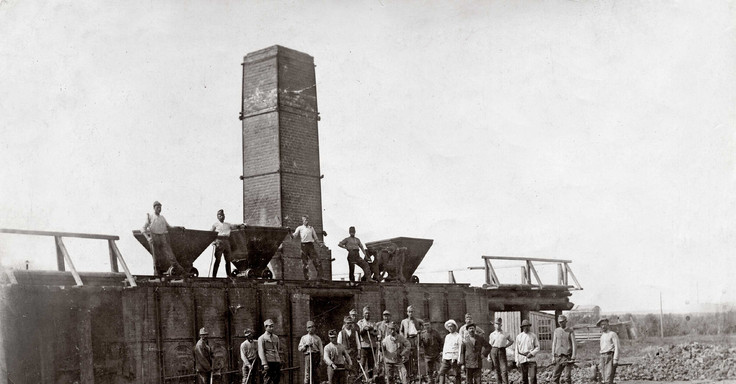

On October 15, 1915, Kopikuz started construction of the plant by its own forces under the guidance of the Belgian consultant Théophile Moiss

Since the plant was built in rural areas, they had to ship all the stuff needed for large-scale industrial construction. Orders for equipment and materials were placed in factories of Donbass, the Urals, England, France, and the USA.

Qualified specialists were recruited in industrial centers of Russia. Because of the shortage of workers, the government allowed Kopikuz to exploit prisoners of war.

The plant was to start production in 1916. But there were too many disruptions in the supply of equipment and materials because of the war. As a result, Kopikuz failed to finish the construction by the appointed time. By 1919 only 70-80% of the plant had been completed.

.jpg)

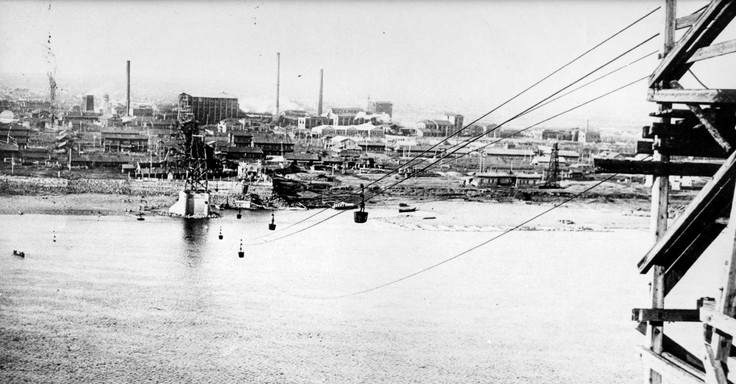

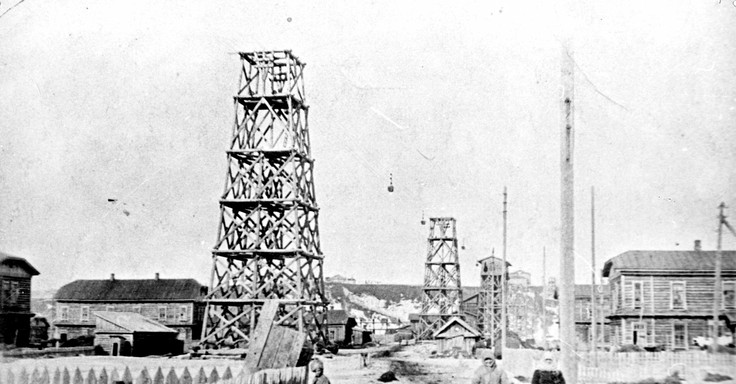

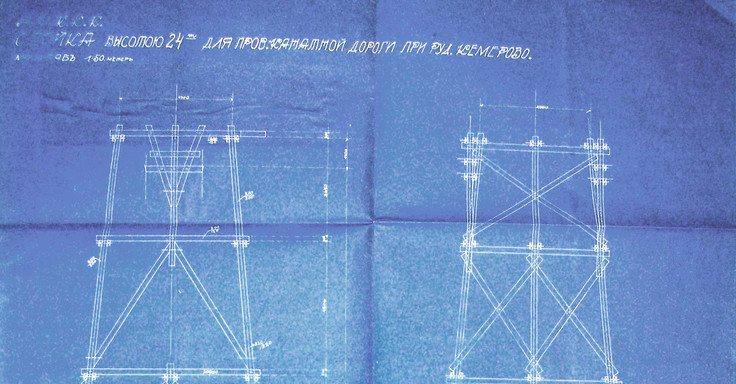

The Lifeline

The cable roadKopikuz built the coke plant and the railway on the gentle slope of the left bank of the Tom’ River. But all the coal mines were located on bluff of the right bank. Coal had to be delivered from the right bank to the left one, but the war conditions prevented the Company from building a real bridge, so it was decided to construct a three-kilometer cable road to connect the Central mine and the coke plant, which took them almost three years (1915 – 1917). Wooden supports were erected on both sides of the river. They were made from larch, and a 405 meter cable was stretched between them. 12 aerial trolleys could simultaneously move at a speed of 2 meters per second from one bank to the other.

In the absence of a bridge, the cable road was used to transport people as well. During ice drift and freeze-up, when it was impossible to use ferries and boats, Kopikuz employees crossed the river in the trolleys.

The cable road became useless in 1933 when a railway bridge was built across the Tom’ river.

Kurako’s dream

The metallurgical plantThe key position in the whole Kopikuz industrial complex belonged to the first large metallurgical mill in Siberia. To develop the project, they invited Mikhail Kurako *, an outstanding Russian metallurgist and the founder of the school of Russian blast furnace production. He agreed to come from Donbass to Kuzbass to realize his long cherished dream: he wanted to build the first large-scale fully mechanized blast furnace shop in Russia. Kurako’s design of the plant was based on the world's largest American metallurgical plant constructed by the United States Steel company in Gary. Kurako’s project was four times smaller in scale, but as well-equipped as its American prototype.

In 1913 the Cabinet granted Kopikuz the exclusive right to explore in the Tel’bes iron ore deposit area. The Company initiated a complex of geological studies conducted by Pavel Pavlovich Gudkov, a young and talented Siberian geologist, and Professor Vladimir Ivanovich Bauman, the founder of the national mining surveying.

Kopikuz bought the Gurievsk Metallurgical Plant, which had been closed by the Cabinet, to use it as an auxiliary plant. They used the shop floor of the restored plant to manufacture new equipment for mines and the coke plant.

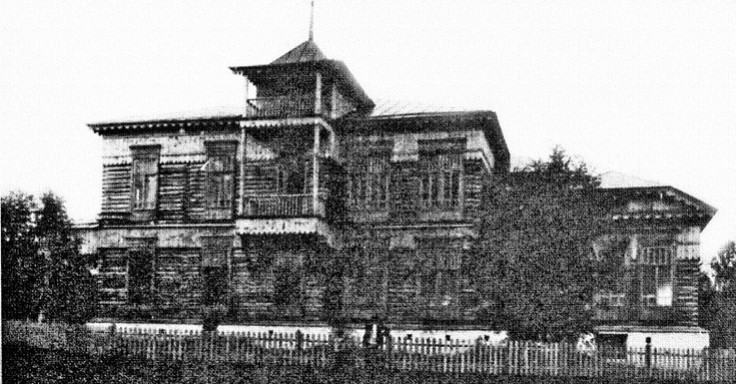

Kopikuz founded a company village in the area of the future metallurgical plant. In 1916, the leaders of Kopikuz invited the famous Siberian architect Andrei Dmitrievich Kryachkov to work as the head of the architectural department and design the factory settlement according to the so-called garden city type. He created a garden city project for the future settlement at the Kuznetsk station on the Kolchugino railway branch.

In its search for funds, Kopikuz turned to foreign metallurgical companies. In early July 1914, Trepov brought to Kuzbass representatives of Schneider-Creusot, a French iron and steel-mill which became a major arms manufacturer. But once again World War I ruined Trepov’s plans.

While Kopikuz failed to find investors for the plant, the Company completed huge groundwork that eventually helped to make the project come true. The Kuznetsk Metallurgical Plant was finally built in the 1930-s in the area chosen by Kopikuz.

«People make all the difference»

The social policy of KopikuzKopikuz was remarkable for its responsible social policy. The Company had to industrialize a remote Siberian province with a predominantly rural population. It had to attract skilled workers and specialists from other regions of Russia.

In 1917, 5758 people worked at the enterprises of Kopikuz: the Kemerovo mine employed 2,448 people; 852 people worked at the coke plant; 1,689 people were employed at the Kolchugino mine; 619 people worked at the Gurievsk factory; 150 people were conducting geological exploration in Kuznetsk and preparing the site for the future iron and steel mill.

Mine work was organized in three shifts: from 6 am to 2 pm, from 2 pm to 10 pm and from 10 pm to 6 am. Drunken miners were suspended from work. In the case of injury or illness, workers received a sick-pay, if approved by the doctor and the department head. All staff and their family members enjoyed free medical aid and medicines.

Sundays and church holiday were days-off. Workers of other confessions were allowed to take days-off on their religious holidays.

To consolidate personnel, construction of industrial facilities was accompanied by residential construction. Company settlements included all necessary infrastructure and institutions; besides, Kopikuz paid local doctors and teachers.

During World War I, Kopikuz kept jobs for all its workers who enlisted in the army and took the care of their families. By order of the Executive Board, the families of the workers who went off to the war were given a monthly allowance that equaled half the salary of the breadwinner; moreover, the family could stay in the company residence up to the end of the war.

Kopikuz provided its employees with "reasonable entertainment" as well. A summer theater operated at the Kemerovo mine. I. I. Lokhansky, the Chief Engineer of the coke plant, organized an orchestra, and musical instruments were purchased at the expense of the Kopikuz Administration. Workers in the factory villages could enjoy cinematographic films.

Due to the social policy conducted by the Kopikuz executives, the situation at its enterprises was relatively peaceful despite all the political turmoil.

In times of war and revolutions

The historical background of KopikuzKopikuz operated in very harsh historical conditions. It enjoyed only a year and a half of peaceful, creative development. In 1914 Kopikuz entered a period of two wars, two revolutions and an endless change of power. Each event had a detrimental impact on its activities.

World War I

World War I ruined all the plans of Kopikuz. It began on August 1, 1914. A large number of workers were called to arms; delivery of construction materials and equipment began to falter as economic relations with foreign countries were getting complicated; it became difficult to obtain bank loans.

Renunciation of the Tsar and the Provisional Government

The next ordeal was the fall of the tsarist regime. On March 2, 1917, Emperor Nicholas II abdicated, and the Provisional Government came to power.

The agreement between Kopikuz with His Imperial Majesty’s Cabinet was canceled. Russian coal manufacturers demanded the abolition of the Kopikuz concession and the introduction of the private property on the former Cabinet lands, the way it was in Donbass. The situation was saved by Fedorovich, who took advantage of the fact that many ministers of the Provisional Government had been his fellow students at the Mining Institute. Not only did he achieve government confirmation of Kopikuz's rights to Kuzbass but he even managed to expand them.

According to the new Charter of the Company, it changed its name: “The Joint-Stock Company of the Kuznetsk Coal Mining Company, established in 1912, continues its existence under the name of the Kuznetsk Coal and Metallurgical Joint Stock Company and aims at the development of coal and ore deposits, as well as of all minerals within the provinces of Tomsk, Yenisei and Irkutsk, trade in these fossils and their products, construction and operation of metallurgical, mechanical and chemical plants. "

The Bolsheviks come to power

When the Bolsheviks came to power in October 1917, it was a hard blow for Kopikuz. By the end of 1918, most of the heavy industry enterprises were nationalized. Kopikuz was saved from nationalization because the Germans seized Donbass, which gave 90% of coal production in the country. Under the threat of disintegration of the coal industry, the Soviet government decided not to nationalize Kopikuz and even issued a loan for its further development.

Under the Bolsheviks, Kopokuz continued its existence as a Joint-Stock Company.

The rule of Kolchak in Siberia

In November 1918, Soviet rule in Siberia was overthrown, and Admiral Alexander Kolchak came to power as the Supreme Ruler of Russia and the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Army. Fedorovich established close cooperation with the new government, signed a contract for coal supply and even opened an office in Omsk. Fedorovich recommended Professor Gudkov, who worked in geological parties in the Kuzbass, as the Minister of Trade and Industry in Kolchak’s government.

The political events put Kopikuz in a difficult situation: in the spring of 1918, Trepov, its Chairman, was shot by the Bolsheviks in Petrograd, while many members of the Board and shareholders managed to emigrate abroad. It was impossible to manage the Company without the general meeting of shareholders, the Board or the Council. As an emergency measure, Fedorovich established a provisional board and became its president. On June 3, 1919, Admiral Kolchak approved a new edition of the Charter of the Kuznetsk Coal and Metallurgical Society and its Provisional Board.

By the end of 1918, Kopikuz stopped paying its employees with cash because of the banking crisis. In January 1919, the Provisional Board began issuing “exchange orders” that circulated as local paper currency in Kemerovo, Kolchugino and the Guryevsky plant.

The victory of Soviet power and the end of Kopikuz

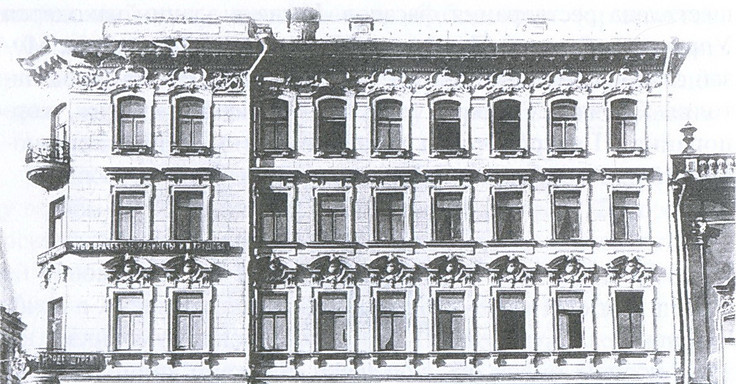

In December 1919, the Red Army restored Soviet power in the Kuznetsk Basin. In early 1920, all coal enterprises in Western Siberia, including Kopikuz, were nationalized. The Soviets created an institution called the Board of Coal Mines of Western Siberia (Sibugol) that was headquartered in Tomsk, in the former Kopikuz office.

The activity of Kopikuz was interrupted at the very peak of its plans. And this is where the capitalist industrialization of Kuzbass ends.

Significance

I. I. Fedorovich described his Kopikuz activities in the following way: "I am creating a project that will fit in any social structure and will be useful for any kind of power."Within the seven years of its existence, the executives of Kopikuz managed a lot, despite the turbulent political and economical situation: they built a railway and coal mines, performed a geological exploration of the coal basin, set up a coke plant and a metallurgical mill.

Of course, the majority of their brilliant plans never came true. Nevertheless, they were able to lay the foundation for a new industrial region of Russia by setting up an example of an integrated approach to the development of a mineral-rich territory.

The strategy designed by Kopikuz was so professional that the Bolsheviks had to follow it even after they had nationalized the Company.

The Soviets completed the railroad construction, finished the coke plant, set up the Kuznetsk metallurgical plant, moved the main coal extraction to the south of the region, and built cities where the company settlements used to be.